Lee Miller- Germans are Like this

Table of Contents

War, Beauty, and Ruin: The Epic Life of Lee Miller

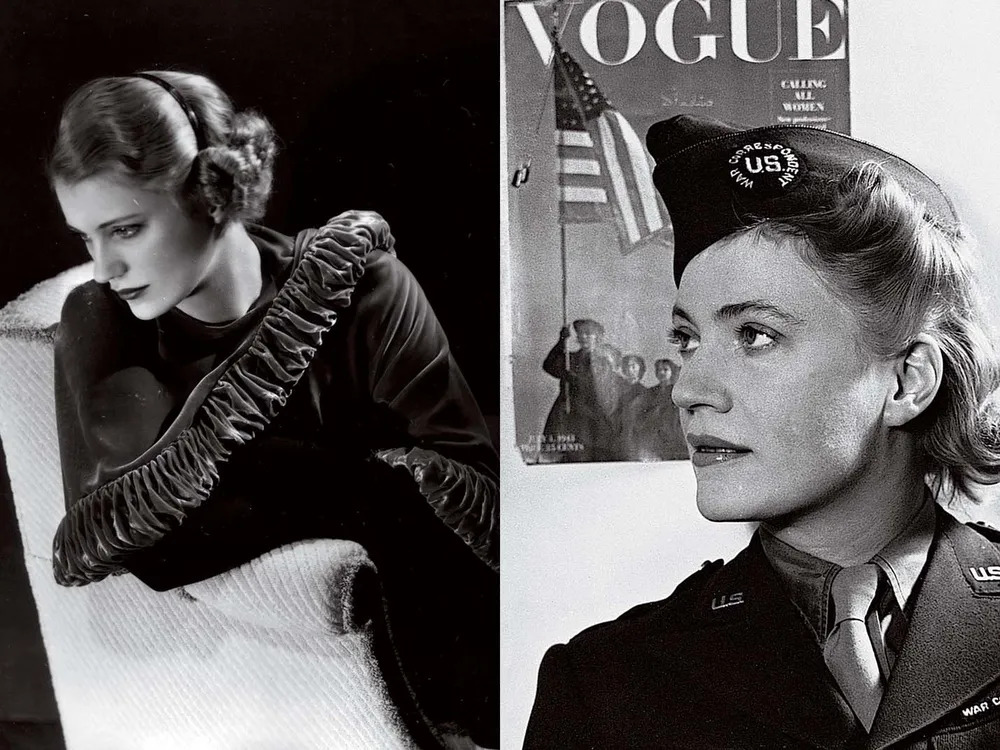

Lee Miller's life was marked by an unusual ability to succeed in sharply contrasting roles — Vogue model, surrealist muse, and war correspondent-photographer among them. Though the idea that she “led many lives” has become something of a cliché, it remains true that she moved between careers, excelling in each. The standard sequence begins with her time as a Vogue model, followed by her Paris years with Man Ray and the surrealist circle. From there, she moved gracefully, and seemingly without strain, into the world of fashion photography.

In 1942, aided by the invisible hands of talent, contacts, and a US passport, she joined Condé Nast Publications as a war correspondent and photographer, following the American army into Europe. Her war work was, for a long time, almost completely forgotten, until her son Antony Penrose began curating her archive with grace and determination. Thanks to his efforts, an extraordinary body of photography came to light, and Miller is now widely regarded as one of the greatest war photographers of the twentieth century. This reassessment has also prompted a broader reappraisal of her other work. A landmark exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in 2015 was a major part of that revival. The Guardian published a striking selection of images from the show here.

It was this rediscovery that led to renewed interest in her life and work, and her inclusion in the canon of great women artists of the twentieth century. Her fame has moved beyond the academy and into popular culture, for example, there is a reference to her in Alex Garland’s film Civil War, where Kirsten Dunst’s character, Lee, acknowledges her as one of the greats. After watching the film, I sought out her article from the June 1945 issue of Vogue, entitled "Germans are Like This"—a piece that reveals her ability not only to photograph but to write with passion and bite. The article, transcribed below, offers a hard counter-narrative to what she feared would become the accepted version of the war. She does not hold back, and it is through this direct, personal voice that we glimpse the emotional landscape of the war’s end, as she saw it in the ruins of German cities.

There is something about the clarity of her style and the starkness of her views that feels out of place today. I was left with the impression that we have lost a particular way of being in the world and that figures like Miller appear to us, in our diminished age, as the heroes of the Iliad must have appeared to Homer’s audience. When faced with monstrous evil, flawed heroes sometimes emerge who remind us of what greatness humanity is still capable of.

To give a fuller sense of her talent, I’ve transcribed the article below, as the original was difficult to read from the PDF. The source is the Vogue archive. Another invaluable resource is the official Lee Miller Archive, maintained by her estate. A thoughtful review of the Imperial War Museum exhibition appeared in the London Review of Books, and is worth seeking out. The original article by Miller is also linked for reference.

Additional Links 📎

- Here is the original article from June 1945 Vogue

- This extract has additional photos from Buchenwald concentration camp under the title Nazi Harvest.

- Review by the LRB of the Imperial War Museum's 2015 exhibition of Miller's war photos.

Figure 1: The many worlds of Lee Miller

The German people — audacious, servile well-fed—have forgotten that they are Nazis, that we are their enemies. Notes on Germany now… By Lee Miller

Germany is a beautiful landscape dotted with jewel-like villages, blotched with ruined cities, inhabited by schizophrenics. There are blossoms and vistas, tiny pastel plaster towns, like a modern water colour of mediaeval memory. There are little girls in white dresses and garlands, children with stilts and marbles and tops and hoops; mothers sew and sweep and bake and farmers plough and harrow; all just like real people. But they aren't. They are the enemy.

The land war was not fought enough on German soil; the punishment for aggression has not yet been sufficiently severe. We thought they'd fight fiendishly, once their own land was invaded, but each house had a white flag on the Nazi banner pole and our armour thrust on, ignoring and by-passing thousands of towns which hadn’t seen a soldier and will remain unimpressed by our might and our men. They are going to find the end and the loss of the war mysterious and inexplicable. The only thing they will understand of it: the casualty lists and the monumental destruction of their cities from the air.

Cologne

My first few days in Cologne were full of disgusting and horrifying encounters. (Cologne edges up and sprawls across the Rhine. The Cathedral looks sourly on a dirty sea of ruin. The great bridge across the river has a broken back.) Reputedly, there were a hundred thousand people living in the vaulted basements of this shell of a city. Very few appeared; those who did were palely clean and well-nourished on the stolen and stored fats of Normandy and Belgium. They were repugnant in their servility, amiability, hypocrisy. I was constantly insulted by slimy German invitations to dine, in German underground houses, and amazed by the audacity of Germans who begged rides in military vehicles and tried to cadge cigarettes, chewing gum, soap. How dared they ? Whom did they think we’d been braving flesh and eyesight against all these years? Who did they think were my friends and compatriots but the blitzed citizens of London and the ill-treated French prisoners of war? Who did they think were my flesh and blood but the American pilots and infantrymen? What kind of idiocy and stupidity blinds them to my feelings? From what kind of escape zones in the unventilated alleys of their brains are they able to conjure up the idea that they are a liberated, not a conquered people?

I’m told that it’s all our fault. We claimed to be waging war on the Nazis, only. Our patience with the Germans has been so exaggeratedly correct that they think they can get away with anything. Well, perhaps they can. In the towns we have occupied, the people grin from the windows in friendly fashion. They are astonished that we don’t wave, or return their smiles. Even before the surrender, the G.I.’s passed cocky young men in the streets, dressed as civilians. They were former soldiers. And there was nothing to do about it.

I don’t know why the Cologne prison is more haunting than others I’ve seen and smelled. In France the execution chambers, one of which was a target range for would-be sportsmen in peace time, had heaps of shot- through, worn-out posts in the back alley. So many bullets had sped through so many Frenchmen that the posts had worn out. Another had ill-concealed mass Boe for men who had been used as game targets, rather like a live pigeon shoot. One had heated walls and the bloody, clawed handmarks of the roasting victims were baked like the designs on pottery. There were scraped messages of courage, defiance, and advice to the new- comer on the cell walls, and the German prisoners iof war who were detailed to dig up the mutilated bodies vomited so much that they were incapable of their task.

The impressive thing about the Cologne jail is that it was in the heart of Germany. These things had been done inside the Fatherland, not by people misbe- having like tourists; nor were they the exaggerations of the licentious energy of a select few who couldn't be traced. These were not the feared SS men or the godly Elite; they were rear echelon Nazi and public government officials, quite normal. This went on in a great German city where the inhabitants must have known and acquiesced or at least suspected and ignored the activities of their lovers and spouses and sons.

Figure 2: Two women in the ruins of Cologne by Lee Miller

There need be no committee to investigate atrocities after this war…no one can be quite fatuous enough to start secret clubs to whitewash German guilt, as they did after the last war. There are millions of witnesse and no isolated freak cases.

My stock question to all Cologne people, “Why didn’t you retreat across the Rhine when the Commander ordered evacuation?” had the classic an- “We are not afraid of the Americans. We lost the war, and it is better to face the last stages on home territory than to retreat indefinitely as stranger refugees, putting off until tomorrow what could be done today.” They hadn’t wanted war. No one I talked to had wanted war. It was those unintelligent Poles who wouldn’t agree to the greater new order who had caused all the trouble. If they hadn’t been so stubborn it wouldn’t have hap- pened, and what business was it of England’s to interfere? No, they weren’t Nazis but naturally they had belonged to the party group.

Aachen

Figure 3: Lee Miller at Aachen Rathaus

Aachen was the first large city to be administered by the Military Government. Aachen continued to be a front-line town for a long time and the inhabitants tasted defeat more bitter than any other city since Paris. Although bombed and rubbled before its capture it had continued to be arrogant and spoiled. The people lived in cellars and vaults, but wore fur coats, silk stockings and fiercely ugly hats. It was the crossroads of the looting of France and the centre, therefore, of the black market. The “City of Cathedrals and Kings” had degenerated into a squalid desolation with a prideless population who hoarded selfishly, cheated in food and had more money than objects to buy; It was bitter to be the first to fall; it was bitter to be prisoners while still believing in victory for the Reich, and they were very caefull to be non- committal about any relief they felt that peace at a price was theirs.

Aachen has been captured and unbombed many months now; ther ehave been no new deaths or burials but it smells and looks like a sepulcure. Civilians go around their daily chores of water-carrying, food hunting, queuing at the few and for between stores for potatoes and vegetables. Newly windowed shops have sprouted in the blasted walls on Theaterplatsz. Fat , pink babies doze in luxurious prams and plain-faced women wait blank-eyed at street crossings while trucks pound the débris of their homes to dust overtheir too good leather shoes and their empty market bags.

In Heidelberg I spent a polite two hours with an American girl who married a German some seven years ago. She was living with her parents-in-law in huge house overlooking the town—an open city, completly untouched. They were enormously rich and I was fascinated by the political mentality of her father-in-law who owned and managed great printing press factories. He claimed entire ignorance of the treatment of slave labour and of the deportation of the Jews. He hid very neatly behind the excuse that we invented for the Germans:that Dr. Goebbels has kept them from knowing the real state of their nation. But the excuse did not just hold in this case: this man had managed a factory where hundreds of slave-labourers worked and he must have known that they lived in guarded camps on starvation rations.

This familylived very well, like all the others I visited in Germany, every house had an electric refrigererator , electric kitchen equipment. The only serious war-shortage seemed to have been textiles. In time of raids clothing was the item most often looted. Big office safes are crammed with the clothes and shoes of families, while company documents are left around in open rooms. I was told in Bruhl that well-bred women didn't wear fur coats during the war, because every factory girl and prostitute was wearing one - stolen from Paris.

No Nazis in Sight

No German has ever admitted to me me that he was a Nazi—not even the little man who was head of the Hitler Jugend in Cologne. They were all party members because they would have lost their jobs otherwise, but no one ever believed in any of it. And the number of Germans who are suddenly are confessing to Jewish rela-tives, and remembering how they sponsored and saved the lives of accused Communists and Anti-Nazis, is grow- ing to ludicrous proportions. I know a Frenchman who actually has met a man who says he was a Nazi. He actually has met a German civilian who says he was proud to be a member of the National Socialist Party, sub- scribed to all its tenets and orders, was in full accordance with chapter and verse of Mein Kampf, and was prepared to be shot or hanged for his principles. Personally, I found him very refreshing, and if he wasn’t in jail a hundred and fifty miles away I'd go and spend a few days in his company. I’m sick and tired of meeting self- styled ignoramuses, with hundreds of party badges in their baggage. Just once I'd like to meet a German who admits that he thought the whole thing was a good idea until it turned out to be a sure loser.